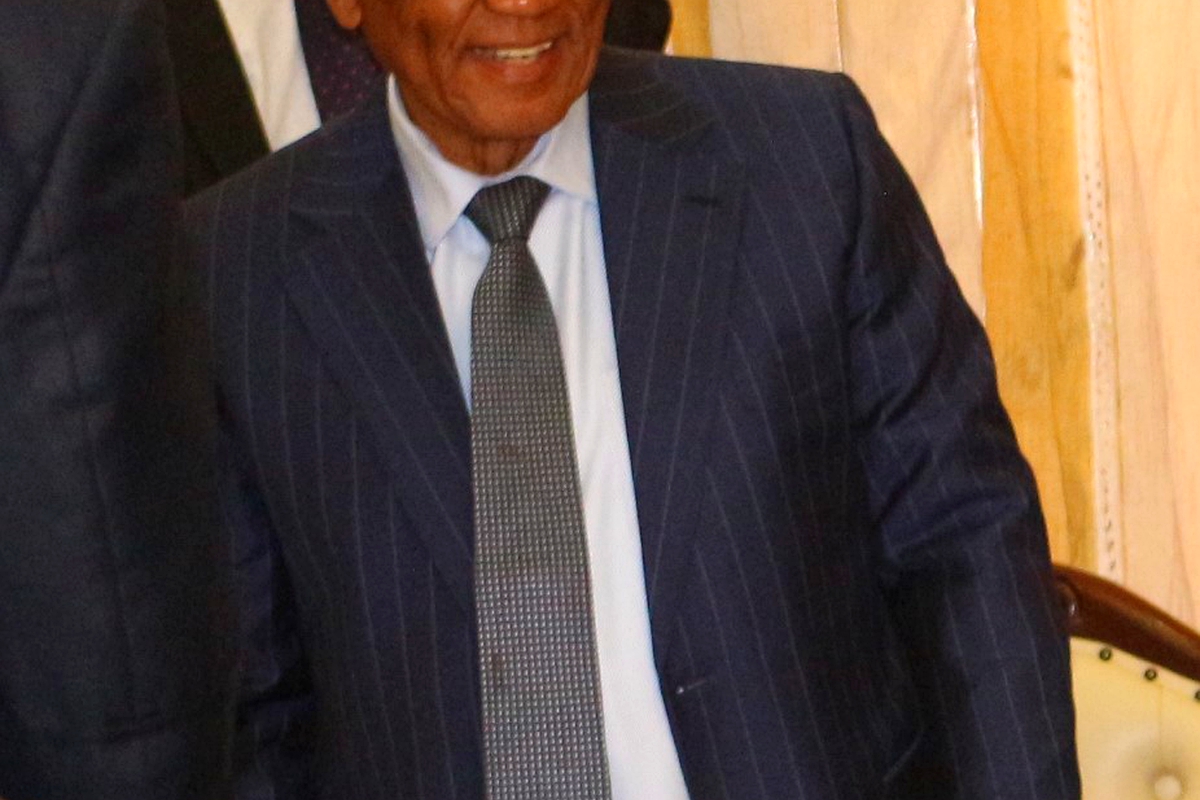

MOLETSANE MONYAKE According to Moletsane Monyake, Lecturer at the National University of Lesotho, Lesotho’s national reform process is in danger of collapse, and a combination of political elites’ contestation for power and control of economic resources, and SADC’s inability to hold them to account is to blame. The Kingdom of Lesotho - a tiny and impoverished country in the belly of South Africa - has experienced recurring episodes of violent conflict over the past 50 years of its independence from Britain. During this period, it has had three coup d’état in 1970, 1986 and 1994, and four attempted coups in 1974, 1998, 2009 and 2014. Following the latest coup attempt in August 2014, and its bloody aftermath, the Southern African Development Community (SADC) put pressure on the Kingdom to undertake constitutional, security sector and governance reforms. These reforms present an opportunity for Basotho to find lasting solutions to their country’s perpetual political crisis. However, the processes of negotiating the reforms and implementing them face several serious challenges. In this article, I demonstrate that Lesotho’s weak economic base and the history of intense rivalry among political elites over access to state power, which is regarded as a vehicle for control of economic resources, undermines elite commitment to the reform process as a collective good. The combination of these two factors - weak historical roots of cooperative politics and the country’s poor resource endowment - has created a situation in which politics is viewed in zero-sum terms, with no room for cooperation and compromise for the greater good. The failure by the political elite to compromise and work together towards a common vision for Lesotho - a fact which underpins the country’s chronic instability as intimated - also acts as the main risk factor of the reforms. In other words, the proposed solution to Lesotho’s political crisis in a form of the proposed comprehensive institutional reforms is, itself, subject to the very collective action problem that underpins this crisis. The constant threat to these reforms is the possibility of an early collapse of the Government as a result of factional infighting within the governing parties. Currently, the All Basotho Convention (ABC) - the largest party in the coalition government - is embroiled in intense factional battles after the faction controlled by Prime Minister (Tom Thabane) and his wife lost control of the party’s National Executive Committee (NEC) during the recent elective conference. Members of the outgoing NEC have refused to hand over the reigns to the new Committee, deploying various tactics to prolong their stay in office. Such tactics have included, among others, an attempt to have the outcome of the elective conference annulled in the High Court, mounting a smear campaign against members of the new NEC and serving its in-coming Secretary General with a letter to show cause why he should not be suspended (and possibly expelled from the party). In turn, members of the new committee and their supporters in parliament, that is, ABC MPs, have taken the battle to the constituencies in order to deepen their support at the grassroots. To the extent that the 2017 snap election was preceded by identical factional battles in the Democratic Congress (DC) - the largest political party in that coalition government - the infighting in the ABC present the most serious threat to both the life of parliament and the national reforms. As a state-building mechanism, the process of undertaking constitutional reforms, especially of the scale envisaged for Lesotho, is a co-operative venture by actors with conflicting private-political interests. The process succeeds when key actors demonstrate the willingness to subject their private interests to the pursuit of the public good of the new constitutional order. This becomes extremely difficult in Lesotho where economic conditions are poor and political interaction is characterised by deep-seated mutual distrust among political elites. Coupled with extreme poverty which raises the stakes for political competition, a long history of inter-elite conflict and betrayals has bolstered the zero-sum nature of political interaction in Lesotho. A history of vindictive and non-accommodative brand of politics has denied the current political actors a cognitive reference point for collective action. Like their predecessors, the current crop of leaders has not internalised the art of compromise which underpins attainment of the long-term goal of national development anchored on political stability. The divisive, acrimonious and vengeful political history of Lesotho puts politicians in perpetual self-preservation mode. Their actions follow the tried and tested script which dictates that acting in the interests of the public is politically costly, as it is seldom reciprocated. It is important to underline the fact that some of the politicians I have interacted with prefer the reforms to succeed, and Lesotho to move away from this suboptimal political equilibrium. Their challenge is that they do not expect their colleagues and rivals to rally behind the reforms in earnest. Furthermore, and most importantly, they are unable to find many like-minded individuals with whom to build a sustainable critical mass of transformative leadership within political parties and across the political aisle. The ultimate result is that commitment to good governance that the new constitutional order seeks to usher in is too costly for reform-minded individuals. Consequently, from time to time, these individuals find themselves having to follow the ‘script’ that everyone else follows, which is to put private-interests ahead of national interests. This locks the political game in sub-optimal self-serving equilibrium which characterises the current reform process. In the absence of historical, cultural and socio-economic incentives for politicians to resolutely see these reforms through, there is a need for exogenously-created incentives for inter-elite cooperation. Fortunately, SADC and Lesotho’s development partners have been acting as providers of that externally organised solution to the collective action problem facing the reforms. SADC has been on the ground in Lesotho since 2014 in its capacity as a conflict mediator and reforms facilitator. Nevertheless, SADC’s ability to enforce collective action in Lesotho leaves much to be desired. The regional body has often failed to break self-serving political gridlocks, due in part to its lack of teeth. For example, SADC-led mediation by the former president of Botswana, the late Ketumile Masire, collapsed allegedly due to refusal by Lesotho’s government leaders to cooperate. In the circumstances, South Africa - a country on which Lesotho heavily depends for economic survival might be the best candidate for the provision of an external solution to the perpetual crisis.

news

April 11, 2019

5 min read

The perilous state of national reforms in Lesotho

Enjoy our daily newsletter from today

Access exclusive newsletters, along with previews of new media releases.

Tailored for you