JOHANNESBURG – SA Chief Justice Mogoeng Mogoeng has been directed by the Judicial Conduct Committee (JCC) to apologise unconditionally for “becoming involved in political controversy” through statements he made during an online webinar hosted by The Jerusalem Post in June 2020 and later at a prayer meeting.

news

March 6, 2021

STAFF REPORTER

6 min read

Why Chief Justice Mogoeng has been ordered to apologise

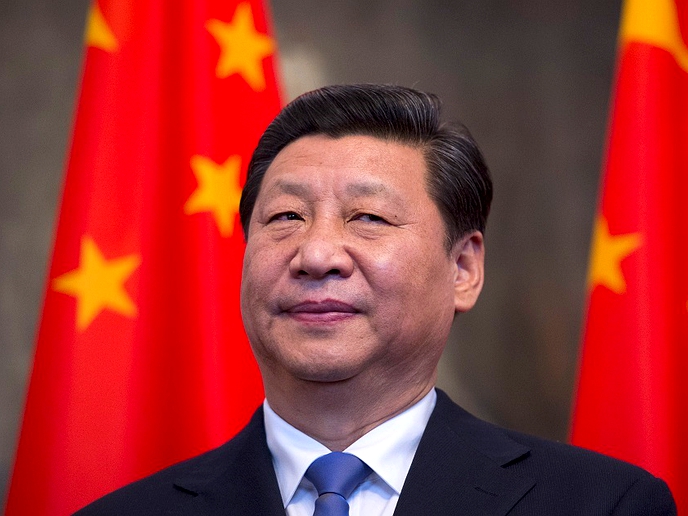

SA Chief Justice Mogoeng Mogoeng

The ruling came after three organisations, Africa 4 Palestine, SA Boycott Disinvestments and Sanctions Coalition and Women’s Cultural Group, laid complaints against him for contravening judicial ethical rules for participating in the webinar with the Chief Rabbi of South Africa.

The complaints also referred to a subsequent comment the Chief Justice made at a prayer meeting in which he refused to apologise for what he said.

The JCC is part of the Judicial Service Commission (JSC) which is responsible for dealing with complaints against judges. The JSC website explains: “Complaints against judges who contravene the Code of Judicial Conduct must first be reported to the JSC Secretariat which is located within the Office of the Chief Justice. The Code of Judicial Conduct provides for ethical and professional standards required of every judge.”

The matter was adjudicated by Judge Phineas Mojapelo.

In his ruling, Mojapelo said questions asked during the webinar required the Chief Justice to comment on matters concerning the diplomatic relationship between South Africa and Israel, which was “clearly political territory”.

He was asked to declare whether he agrees with the foreign policy of his country towards Israel. “He cannot enter that terrain without entering the field of political activity, and he cannot differ with those who are in charge of that policy, without controverting political leaders in that field,” Judge Mojapelo said.

“He responded that while the laws are binding on him, he said like any other citizen, he is entitled to criticise the policies of South Africa or even suggest that change is necessary.

“Whether we like it or not, the Chief Justice is not like any other citizen of South Africa. He is the head of the judiciary and is subject to the restraints of that office, including the ethical rules which govern the conduct of each and every single judge. He is subject to those restraints of his office in his official and private capacity,” Judge Mojapelo said.

Mojapelo said at the time that the Chief Justice made the utterances, he had been fully aware of South Africa’s foreign policy position on the Israel-Palestine conflict and yet he had criticised it and suggested what should be changed.

“There is no scope to argue that his conduct was not willful or grossly negligent,” wrote Mojapelo.

What aggravated the matter was the comment he made when called upon to retract what he had said at the webinar.

At a later prayer meeting, he refused, saying there was nothing to apologise for.

Even in his response to the JCC, he repeated: “I stand by my refusal to retract or apologise for any part of what I said during the webinar. Even if 50 million people were to march every day for ten years for me to do so, I would not apologise. If I perish, I perish.”

Judge Mojapelo said he repeated these words at a time when he was aware that the committee had been investigating the complaints for three months.

“It was an opportunity for him, as leader of the judiciary to publicly declare his confidence in the statutory processes of the committee. His statement did the opposite, exuding a self-righteous view that he would only apologise if he believed himself to be wrong.

“Members of the judiciary have a duty individually and collectively to publicly accept their own peer review process and to strengthen its credibility. Instead, he showed his disregard for the process by flaunting the fact that he would never apologise for his conduct, even if 50 million people marched for ten years.”

Judge Mojapelo said it appeared that the Chief Justice was being “brazenly defiant” and it was important, in order to maintain the public image of the judiciary to its rightful place, that he be ordered to apologise and retract what he said at the webinar and the prayer meeting.

The JCC’s order

Mojapelo’s full order reads:

The respondent CJ shall issue an apology and retraction worded as follows:

Apology and Retraction

Enjoy our daily newsletter from today

Access exclusive newsletters, along with previews of new media releases.

I, Mogoeng Mogoeng, Chief Justice of the Republic of South Africa, hereby apologise unconditionally for becoming involved in political controversy through my utterances in the online seminar (webinar) hosted by The Jerusalem Post on 23 June 2020, in which I participated.

I further hereby unreservedly retract and withdraw the following statement which I uttered subsequent thereto or other words to the same effect: “I stand by my refusal to retract or apologise for any part of what I said during the webinar. Even if 50 million people were to march every day for 10 years for me to do so, I would not apologise. If I perish, I perish.”

I reaffirm my recognition for the statutory authority of the Judicial Conduct Committee of the Judicial Service Commission established in terms of Part 11 of the JSC Act 9 of 1994 to decide on any complaint of alleged judicial misconduct against me and all judges in the Republic of South Africa.

The respondent CJ must, within ten (10) days of this Decision read the above Apology and Retraction at a meeting of serving Justices of the Constitutional Court and release a copy thereof under his signature to the OCJ and to the media in the normal manner in which the Constitutional Court and the OCJ issue media releases.

GroundView: What now?

By GroundUp Editors

The Chief Justice, with only a few months left before he retires, now faces an unprecedented sanction. He could drag matters out and appeal the ruling — in which case the full JCC will have to rule on the matter.

If he chooses to defy the order he will almost certainly have to resign, and that may be insufficient to escape further sanction. Even if he abides by the decision and makes the apology, it’s unlikely he will continue to have the confidence of the judiciary.

And this was not the only controversial matter he waded into for which he may be sanctioned. His questioning of the efficacy of Covid-19 vaccines is also the subject of a judicial complaint by an advocacy group called African Alliance. DM

Tailored for you