A crisis simmers in Southern Africa as the landlocked country formerly known as Swaziland cracks down on pro-democracy demonstrations.

africa

July 29, 2021

TUCKER C. TOOLE

5 min read

Africa’s last absolute monarchy is shaken, as protestors defy Eswatini’s king

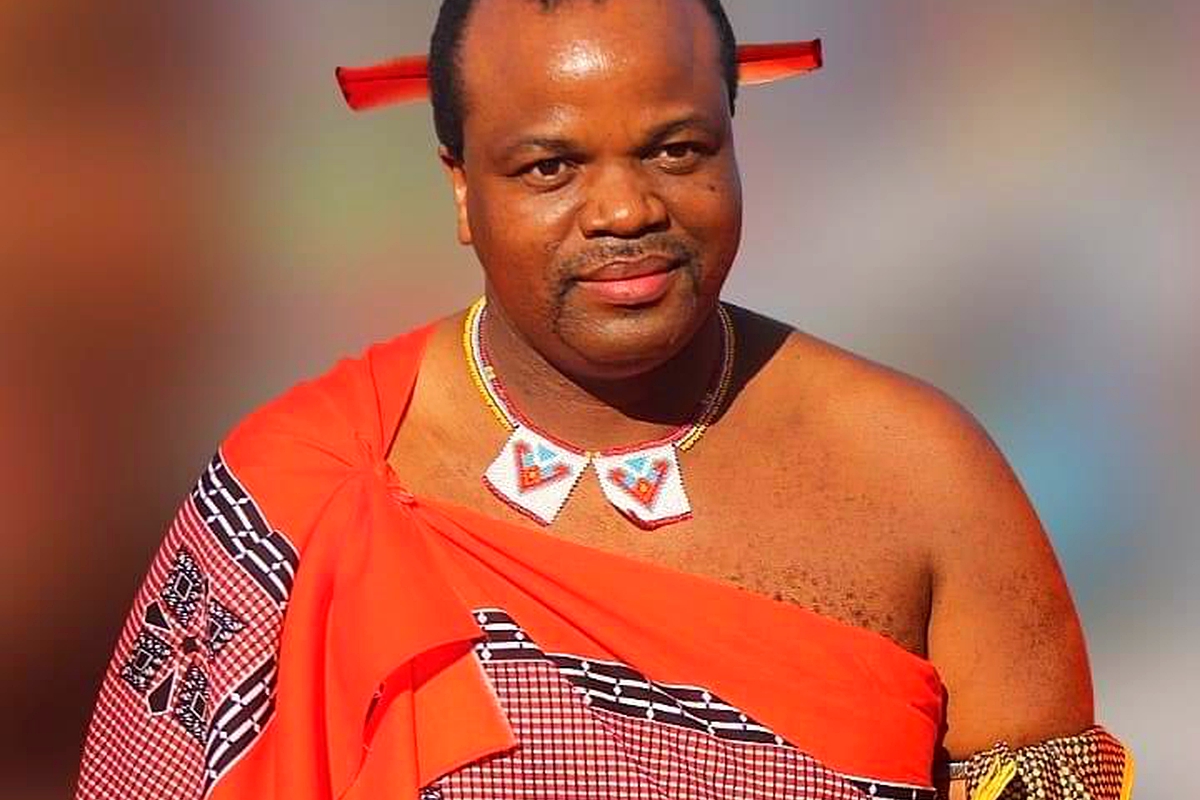

King Mswati III of eSwatini

One nation is making its Olympics debut in Tokyo. Formerly known as Swaziland, the Kingdom of eSwatini - Africa’s last absolute monarchy - will be represented when four of its athletes go for the gold in track and field, boxing, and swimming.

While these citizens compete in Japan, many of their family, friends, and fans back home in Southern Africa are engaged in an entirely different struggle - one with far-reaching, and deadly, consequences.

For the past two months, Eswatini has been gripped by unrest as pro-democracy protestors have taken to the streets to call for political reform and express dissatisfaction with the rule of King Mswati III, Africa’s last absolute monarch.

These protests were triggered following the death of 25-year-old law student Thabani Nkomonye, who was allegedly killed by the Eswatini police. Since then, at least 40 additional people have died and more than 150 protesters have been hospitalised with injuries resulting from police shootings, beatings, and excessive use of force.

In response to the protests, the eSwatini Communications Commission suspended access to social media and online platforms until further notice. This action prevented citizens from documenting the police violence that was taking place. The government clampdown has also limited access to journalists covering the protests.

From Swaziland to Eswatini

For much of the 20th century, this small, landlocked country was under British control, finally gaining its independence in a nonviolent transfer of power in 1968.

In 2018, to mark the nation’s first half century and to dispose of the country’s colonial past, its king announced that the land formerly known as Swaziland would henceforth be known as the Kingdom of Eswatini.

“African countries, on getting independence, reverted to their ancient names,” King Mswati III told the crowd during the announcement. He was pointing to a return to traditional or historical names from “before they were colonized.”

The king has now ruled the nation, which shares borders with South Africa and Mozambique, for 35 years. Political parties are banned and nearly two-thirds of the country’s 1.2 million people live below the poverty line, according to the World Bank.

As Stephen Leahy previously reported for Nat Geo, King Mswati III had long complained that people outside of Africa confused his country with Switzerland. But while Eswatini, “the land of the Swazis,” does have some mountains it’s much smaller; in fact, it’s smaller than New Jersey. Unlike Switzerland’s direct democracy, King Mswati inherited the throne in 1986 from his father, Sobhuza II, who had reigned for 82 years.

In recent years, Eswatini has stirred controversy over its efforts to engage in the rhino horn trade. At the 2019 Conference of Parties to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), Eswatini proposed to reopen legal international trade in white rhino horns. The kingdom can already trade limited amounts of live southern white rhinos, as well as hunting trophies, but its proposal to enter international commercial trade in rhino horn, which is currently forbidden, was soundly rejected.

As reported by NPR, Eswatini continues to struggle with COVID-19, which has caused nearly 700 deaths, and the government is struggling to pay teachers, a problem that led to protests earlier this year. As the news outlet notes, “the king and his 15 wives continue to live an opulent life.”

The reigning royal is learning that changing the name of an impoverished nation proves not to be a panacea for its people. Even as its new name aims to reclaim ancestry in an effort to stir national pride, many of the country’s citizens are more focused on the future as they engage in protests against the continent’s last absolute monarch.

“We are the youth of Swaziland and we are so much depressed by the government,” a young protester told Al Jazeera in June. “Our government is not being fair; it is just a one man’s land.”

The current state of civil unrest

Enjoy our daily newsletter from today

Access exclusive newsletters, along with previews of new media releases.

In response to the protests that have roiled Eswatini, King Mswati III announced that former pension fund boss Cleopas Dlamini would replace Prime Minister Ambrose Dlamini, who died in December after contracting COVID-19. The announcement was made following demonstrations demanding the right to democratically elect a prime minister, among other reforms.

“I have prayed that I have a man that would bring the country to normalcy, restore the country and resuscitate the economy,” Mswati told crowds. Nonetheless, BBC reports, the king has described anti-monarchy protests as “satanic,” noting that they had taken the country backward.

As set out in a 1972 decree, the nation’s political system does not legally recognize political parties and they are not permitted to contest elections. This means that, when running for parliamentary seats, candidates must run independently, without the backing of a party. In the past, political dissent has not been tolerated, with activists and trade union leaders silenced by harsh laws.

“However, with dissent growing, there is a convergence of previously disparate demands, with citizens rejecting Mswati's autocratic rule - namely, his sole authority to appoint a prime minister, his executive power over the parliament and the judiciary, and his right to act as sole custodian of all land in Eswatini,” reports NPR’s Tendai Marima.

It will take more than the appointment of a new prime minister to address the nation’s concerns. In an interview with BBC News, journalists who have faced the government crackdown described their experiences covering the news in a nation engulfed in turmoil.

Journalist Magnificent Mndebele feared for his life as he was physically beaten by authorities. “They were strangling me, like holding me by my throat and then putting me down…others were punching me in my ribs,” Mndebele told BBC News.

Cebelihle Mbuyisa, a reporter for New Frame who was working alongside Mndebele, tried to document the violence by taking pictures on his cellphone. “But then [a] soldier jumped out of nowhere and ordered us [to] come over… He wanted to know why we’re taking pictures here.” The soldier said it was illegal to take photos, allegedly due to the Eswatini Communications Commission’s suspension of media access.

“But we told them that we’re journalists,” said Mbuyisa. “And they didn’t seem to care.”

National Geographic

Tailored for you