LESOTHO went to the polls on October 7, 2022. Or at least some of its voters did. Turnout was at an all-time low of 38% of registered voters. Many are expressing discontent with politics in Lesotho by refusing to participate. Those that did come out were in an anti-incumbent mood.

politics

Oct. 24, 2022

OWN CORRESPONDENT

5 min read

Turnout down to 38% in Lesotho elections

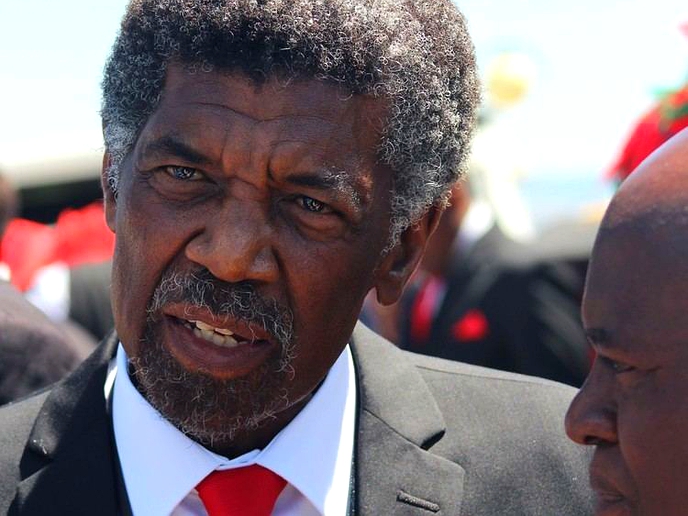

RFP leader, Sam Matekane

Story highlights

This turnout was almost 10 percentage points below the 47% who voted in the last elections in 2017.

Sam Matekane, a wealthy businessman who has never been engaged formally in politics before this year, emerged as the new prime minister.

At 64, he’s much younger than the men who have hitherto dominated politics in Lesotho – Tom Thabane was 81 when he was forced to resign in 2020 after being charged with the murder of his ex-wife; Pakalitha Mosisili was 72 when he left office for the last time in 2017. Only Moeketsi Majoro, 60, whom Matekane succeeds, is younger than him.

Matekane’s Revolution for Prosperity (RFP), a party formed only in March, won 56 seats out of 120 in parliament. He combined with two smaller parties, the Movement for Economic Change (MEC) and the Alliance of Democrats (AD), to form a governing coalition.

All the parties that had been in the last parliament lost some seats.

The All Basotho Convention (ABC), the party occupying the prime minister’s office from 2017 to 2022, fell from 48 seats to eight.

The last parliament failed to pass a series of political and security forms. Those bills would have ended parliamentary representation for tiny parties and curbed the power of the prime minister.

The prime minister’s power to appoint the judiciary, for one thing, means that Basotho perceive politics as a rigged game in favour of those with power and connections.

Voters hope Matekane’s coalition will prioritise passing reforms.

Matekane’s victory is, perhaps, Lesotho’s last and best chance to actually enact the political reforms that will allow the country to move forward from a decade of political malaise and non-governance. Voters are tired of the old politicians and their unwillingness and inability to solve the pressing problems of poverty, crumbling infrastructure and social service under-investment.

While Matekane’s party won a majority of the directly elected seats, it still polled under 40% of the total vote.

This is because Lesotho, a country of about 2.1 million people, has 65 registered political parties. No party can command a majority. This has led in the recent past (2012-2022) to ever-shifting coalitions and repeated changes of government. Hence, general disillusionment.

The election turfed out many established politicians, with only the main opposition Democratic Congress (DC) reaching double-digit numbers of parliamentary seats.

The RFP poached a few established politicians to run, but largely relies on the rags-to-riches story of founder Matekane for its appeal. One of 14 children in his family, he was born in a rural village in the mountains near the town of Mantsonyane.

He left school before completing secondary education and built a business empire. Starting in road construction and mining transport, the company diversified into real estate, aviation and more.

Matekane himself kept a low profile for many years, but in the past few years has increased his public visibility through charitable giving and as chair of a private sector group working to get more COVID-19 vaccinations to Lesotho.

Matekane will be challenged to work within a parliamentary system where he, as prime minister, will have plenty of power but not absolute control as he did in business. The art of compromise will be one he needs to master, and quickly.

He has come to office saying the right things about ending corruption, making government more transparent, and reforming a political system prone to gridlock and quick shifts of government. If he manages to finally pass the national reforms that stalled in the last parliament, the weary electorate in Lesotho will likely reward his party handsomely.

If, however, his party falls into infighting, the electorate could continue to lose hope in democracy as a means of governance.

The party’s inability to win an outright majority means another coalition. Its partner AD is led by long-time politician Monyane Moleleki, who said in April that he had “made” Matekane by steering his companies’ government contracts.

The other coalition party, the MEC, is led by Selibe Mochoboroane, who currently faces treason charges related to the 2014 coup attempt.

Both leaders are seen as linked with the fractious coalition politics of the 2012-2022 period. Some Basotho are disappointed that Matekane had to include them in government.

The bigger question is whether the RFP can push through amendments to the constitution. They were mandated by the Southern African Development Community (SADC) after repeated attempts to settle Lesotho’s political feuds dragged on for much of 2017-2022.

The last parliament then failed to pass them. They would have limited the power of parties and individual members of parliament. The new coalition promised to quickly pass them. Its popularity, somewhat ironically, will rest on curbing its own powers.

Enjoy our daily newsletter from today

Access exclusive newsletters, along with previews of new media releases.

No matter what the government does, the Lesotho populace is hurting from the continued effects of the COVID pandemic. The border shutdown during the pandemic meant hardship for much of the population which is still largely dependent on migrant labour to South Africa.

The textile factories in Maseru have retrenched around 20 000 workers, leaving only about 30 000 employed there now. There are few other secondary industries. Government is the major employer, and Matekane said he would bring “austerity” to the national government.

Unable to change the country’s fundamental vulnerability to shifts in the global and regional economy, Matekane has few economic levers to pull. He will have to rely on his own personal persuasiveness. Even more difficult, he needs to get parliamentarians to limit their own personal power, and convince citizens he has changed the system.

Many Basotho put their faith in the local champion from Mantsonyane who beat the odds to become the country’s richest man. His term as prime minister could bring about a more stable and better-governed Lesotho. – The Conversation